Landowners need more information on Marcellus Shale drilling

Monday, February 7, 2011

By ANDY ANDREWS

Contributing writer

STATE COLLEGE, Pa. — During a portion of the Farming for the Future Conference at the Penn Stater Conference Center Feb. 4, a forum explored Marcellus Shale drilling issues and was informative, and at times, divisive.

Issues

Several speakers cut through the emotions and issues regarding drilling through the Marcellus shale to extract natural gas in Pennsylvania. The forum topic was The Effects of Marcellus Shale Development on Our Farms and Communities. The consensus of the panel was that haphazard approaches to drilling for natural gas could leave precious resources vulnerable to contamination and ruin.

“Clean water is the lifeblood of a farm,” said panelist and organic produce grower Al Benner, of Old School Farm in Honesdale, Pa. “If we don’t have clean water, we don’t have anything.”

Improper drilling could pollute surface and groundwater, which could then jeopardize the workings of sustainable agriculture everywhere in the state, according to the panelists. Tracy Carluccio, deputy director of the Delaware Riverkeeper Network (www.delawareriverkeeper.org) in Bristol, Pa., said Pennsylvania occupies the largest land mass — 36 percent — of the total Marcellus Shale area. The Delaware River watershed is part of that landmass.

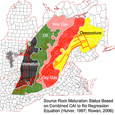

Overall, 63 percent of the Marcellus Shale landmass — the name originates from Marcellus, N.Y. where the shale literally pops out of the ground — occupies areas of Pennsylvania, Ohio, New York and West Virginia, to the tune of 48,000 square miles, the largest shale formation in the U.S.

The Northeast uses 13 trillion cubic feet of natural gas per year out of a total of 23 trillion cubic feet, according to Michael A. Arthur, co-director the Marcellus Center for Outreach and Research at Penn State. Arthur, along with Tom Murphy, co-director of the Center, was scheduled to present a forum on the science and impacts of development on the Marcellus Shale landmass Feb. 5 at the conference.

Desirable

Because of a very “beautiful” natural gas pipeline system in place in the Northeast, the natural gas formation is very attractive to companies who realize the transportation cost savings to cities such as Boston, New York, Philadelphia and Washington, D.C., according to Arthur.

According to Jan Jarrett, president and CEO of PennFuture (www.pennfuture.org) in Harrisburg, Pa., Northeast markets use 40 percent of the gas extracted in the U.S.

“It’s a very profitable gas field for drillers,” Jarrett said. Jarrett noted the pace of drilling has accelerated in the past three years. Rules written last year have spurred innovative technologies to re-use the waste water and construct well pads with greater construction integrity.

A thoroughly developed and tested “bar of excellence” is needed in construction and maintenance of the drilling sites to ensure environmental integrity, according to Jarrett. In October 2010, an executive order was signed by then-Pennsylvania Gov. Ed Rendell to ban additional Marcellus Shale drilling leases until more studies are done on the environmental impacts. The ban is expected to be rescinded by Governor-Elect Tom Corbett.

Carluccio said the Marcellus Shale land mass is 380 million years old. About 95-98 percent of the available gas that can be extracted from the shale formation is methane. The actual shale formation, resting horizontally more than a mile underground, is only about 25 to 250 feet thick.

Process

But technological advances have allowed a system of horizontal drilling that uses compressed water with a mixture of sand and silicon with other chemicals, at 15,000-22,000 pounds per square inch, to create “fractures” in the shale where gas can be extracted. According to Arthur, the pressure is created by a 22,000 horsepower system.

There is a potential in the state for 30,000 well pads covering 30,000 acres at one per acre. A well pad operates like the center of a bicycle wheel, with “spokes” that are drill lines. The gas is collected up a single pipeline and stored in tanks. The water used to drill is supposed to be reclaimed and used again, but there is potential for spills that could result in surface and groundwater pollution — thus threatening farms.

Carluccio said the chemicals include many known carcinogens that could drastically threaten human and livestock health. Regulations are still sparse when it comes to creating and maintaining wellhead protections up to standards, and those standards need to be clarified and enforced, according to Jan Jarrett, president and CEO of PennFuture.

Carluccio noted her organization and others are “very concerned” about the cumulative impacts to the environment and the communities where the drilling takes place. Estimates by her organization noted the level of violations is “outstanding,” with three-quarters of the wells drilled so far in “violation of existing regulations,” she said. “We cannot sacrifice one resource for another, we cannot sacrifice our water for gas.”

Benner, the Honesdale, Pa. grower, spoke about the importance of the Dyberry River to his farm. The Old School Farm itself is in a flood plain with a high water table. If there is a shale drilling water spill, “what will settle in my valley where my crops are growing?” Benner asked.

Benner maintains the 54-acre farm with his wife Deena and twin sons Owen and Coleman, 5 years old. Benner also operates several businesses near Philadelphia, but he and his family have grown up and live entirely in the Delaware River watershed.

“We need to stop sitting here and saying it’s just going to happen,” he told those at the forum. “It’s going to have to happen on our terms if it’s going to happen at all.” He wants to stop the amount of “disinformation” that is being provided by drilling companies to landowners to extract the gas as quickly as they can.

Concern

The major concern that Benner has: where is the drilling wastewater going to go, and how is it going to be kept from polluting fresh water wells? “We don’t have to rush in and do things haphazardly and take risks,” he said. Benner said he was upset at the local and regional newspapers and other organizations who constantly talk about the upside of the drilling rather than the dangerous risks.

Most homeowners in the watershed don’t have legal options — or really many options at all — if their drinking and irrigation water becomes contaminated. Benner was concerned about the recent “rush” to have leases signed, almost in effect ensuring their places and having a “grandfathering” effect on heavier regulations that will inevitably come down the pike.

But according to Arthur of the Marcellus Center for Outreach and Research, it is important to know that many companies are adopting better water collection and wellhead construction techniques to ensure the environment is protected.

To contact Arthur, call 814-865-1587 or e-mail maa6@psu.edu. To contact Jarrett, call 717-214-7920 or e-mail Jarrett@pennfuture.org. To contact Carluccio, call 215-369-1188, ext. 104 or e-mail tracy@delawreriverkeeper.org.