Pa. study: If you get a shale check, will you stop milking?

Saturday, March 3, 2012

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — There may be a link between natural gas development and a drop in dairy production in Pennsylvania’s Marcellus Shale region, but the exact reasons for the decline are unclear.

According to researchers in Penn State’s College of Agricultural Sciences, anecdotal evidence has suggested that natural gas development is benefiting many Pennsylvania farmers, with money from gas leases and royalties allowing producers to pay off debt, invest in new equipment and remain active in a business often characterized by razor-thin profit margins.

Still other reports have indicated that some farmers are using gas-related income to make major changes to their operations or to leave agriculture altogether.

However, little data exists to measure the true impact of natural gas development on agriculture in the state.

Studying dairy numbers

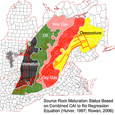

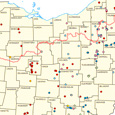

To get a better picture of how the natural gas boom is affecting Pennsylvania’s top agricultural sector, dairy farming, researchers led by Timothy Kelsey, professor of agricultural economics, examined county-level changes in dairy cattle numbers and milk production between 2007 and 2010, as reported by USDA’s National Agricultural Statistics Service. (Read the report: Pa. Dairy Farms and Marcellus Shale, 2007-2010.)

Those data were analyzed in connection to the level of natural gas drilling activity in each county, as indicated by Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection statistics on the number of wells drilled during the same three-year period.

“Changes in dairy cow numbers seem to be associated with the level of drilling activity,” said Kelsey.

Counties with 150 or more Marcellus Shale wells on average experienced a nearly 19 percent decrease in dairy cows, compared to only a 1.2 percent average decrease in counties with no Marcellus wells, he said.

Milk production followed a similar trend.

More wells, less milk

Production in counties with at least 150 Marcellus wells fell by an average of 18.5 percent, Kelsey said. In contrast, milk production in counties with no Marcellus wells increased by about 1 percent.

For example, in Bradford County — which had more than 500 drilled Marcellus wells and ranked sixth in the state in dairy production — cow numbers and milk production both fell more than 18 percent during the period.

On the other hand, Chester County, the fifth ranked county in dairy production, had no Marcellus activity and saw cow numbers and milk production rise by 7.4 and 9.3 percent, respectively.

Overall, the report states, only two of the 19 counties with 10 or more Marcellus wells had an increase in cow numbers or milk production between 2007 and 2010.

Meanwhile, 15 of the 33 counties with no Marcellus activity experienced an increase in cattle numbers or milk production.

Not huge, overall

Kelsey pointed out that county-level declines did not necessarily have a major effect on statewide production numbers, since much of Pennsylvania’s agricultural activity takes place in the ridge-and-valley regions of the state, rather than in the Marcellus Shale region on the Allegheny Plateau.

“Only two of the top 10 agricultural counties as measured by sales have Marcellus Shale beneath them,” he said.

“The six counties with the most Marcellus wells together account for about 5 percent of all agricultural production, while the 33 counties with no wells account for 79 percent of the state’s agricultural activity.”

But regardless of how a county ranks in statewide production, “agriculture plays important local economic, environmental and social roles, so it’s important to understand the implications of Marcellus Shale development on farming.”

Too many unknowns

Kelsey maintains that additional research is needed to understand the dynamics of what is occurring. He said the available data can’t pinpoint whether these declines resulted from existing farms simply downsizing their herds, whether some farms ended dairy production but shifted to other agricultural enterprises, or if they exited farming altogether.

He also noted the importance of knowing whether those farmers who are leaving agriculture due to Marcellus development are doing so voluntarily.

“Are they taking the money, paying off farm debt and choosing a new vocation? Or are they being forced out of farming due to environmental or other concerns, such as negative effects on land, water or herd health, or consumer resistance to food originating near natural-gas wells?”

Bigger economic picture

The implications of lower cow numbers and milk production go beyond the farmers involved, Kelsey explained.

“Declining cow numbers mean fewer dollars spent locally by farmers to maintain their herds,” he said. “At the same time, lower milk production means fewer dollars coming to the local economy from milk sales.

“A variety of businesses depend on local farms for their success, including feed stores, veterinarians, machinery dealers, milk haulers and dairy processors,” Kelsey said. “If the number of farms and associated agricultural activity fall too low, essential supporting businesses will go away, making it difficult for remaining farmers to access the inputs and markets needed to remain in business.”

Reinvesting in farm

Kelsey said future research should investigate whether farmers who receive lease and royalty payments and choose to stay in agriculture are using gas-related income to improve their farms.

“Anecdotes from farmers, equipment dealers and bankers suggest that some farmers are using proceeds from Marcellus activity to strengthen their operations, which has the potential to benefit the agricultural economy,” he said.