Deep-well drilling boom creates concern for Pa.’s water resources

Sunday, August 24, 2008

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — The current boom in natural-gas well drilling is reminiscent of Pennsylvania’s halcyon days of oil production and coal mining early in the last century.

But along with that boom, comes a concern for the state’s streams and groundwater.

“Decades ago, we weren’t careful with coal mining,” said Bryan Swistock, water resources specialist with Penn State Cooperative Extension. “As a result, we are still paying huge sums to clean up acid mine drainage from that period, and we will be for a long time.”

“We need to be careful and vigilant, or we could see lasting damage to our water resources from so many deep gas wells being drilled across Pennsylvania.”

Going down

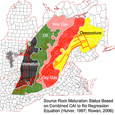

This latest wave of gas-well drilling is unlike other previous exploration because the wells are so deep, tapping the Marcellus shale formation, which is a mile or more below the surface of much of Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Ohio and New York.

Scientists have known for years the gas was there, but it wasn’t until new drilling technology was developed that it could be extracted. This method uses hydraulic pressure to fracture the shale layer so trapped gas can escape.

‘Fracking’ water

“Fracking, as they call it, can require several million gallons of water for each gas well, and some wells may be fracked more than once during their active life, which might span more than a decade,” Swistock said.

“Where that water comes from, and what the drillers do with it when it is recovered, is a big issue for our state.”

Swistock said the fracking water can have various chemical additives along with natural contaminants from deep underground when it comes back to the surface. He said it needs to be collected and treated or recycled properly.

In other states, fracking water has been found to contain numerous hazardous and toxic substances, including formaldehyde, benzene and chromates. Most municipal sewage-treatment plants can’t or won’t accept gas-well waste fluids.

Natural radioactivity

Another potential hazard from gas-well wastewater is the release of radon and other naturally occurring radioactive materials, said Swistock.

“Radioactive substances are not uncommon in Pennsylvania groundwater to begin with,” he said, adding that the waste fluids that come with gas production also may contain high levels of salt, various metals such as iron and manganese, and traces of barium, lead and arsenic.

“Although highly diluted with water, the proper treatment of all gas-well waste fluids is a big issue that needs to be addressed.”

Test your wells

People who live close to gas-drilling operations should have their water tested by a third-party, DEP-approved lab, advises Swistock.

“Homeowners who have their own well or spring and are within 1,000 feet of a gas-well site are very likely to be visited by water-lab employees hired by the gas company,” he said, adding that homeowners should take advantage of this free testing and make sure to get copies of the results, which they are entitled to by law.

If homeowners decide to do their own water testing, it’s important that they have an unbiased expert from a state-certified lab collect the samples in case the sample results are needed for legal action, he said.

The timing of sampling is important, according to Swistock. Well owners should have their water tested within a few months prior to the start of the drilling. Once a company has started drilling, it’s too late because there won’t be a record of the well water’s quality before drilling.

Who’s responsible?

If a resident decides to test for any impacts after the drilling has occurred, that needs to be done within six months because drillers are presumed responsible for any damage to water supplies within six months after drilling has begun.

“Although we have occasionally seen effects on water supplies beyond 1,000 feet, the regulation that is written into the gas and oil act states that any water supply within 1,000 feet of a gas well is the driller’s responsibility for six months after drilling,” he said.

If there is any complaint, the driller is guilty until he is proven innocent; outside the 1,000-feet distance and six-month time frame, the burden of proof shifts to the homeowner.

Where’s water source?

While contamination from waste fluids is one concern, another is where the companies will get all of the fresh water they need for drilling and fracking. Swistock warns that taking too much water from headwater streams may disrupt sensitive aquatic ecosystems.

“Two drilling operations in Lycoming County recently were shut down by the state Department of Environmental Protection because they were drawing huge volumes of water from small streams in violation of the Clean Streams Law.”

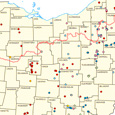

Complicating the water-usage issue is differing oversight across the state. Both the Delaware River and Susquehanna River Basin commissions require permits from well drillers who plan to withdraw large amounts of water. The Ohio River basin currently has less oversight.

Not black and white

Growing up in Indiana County, Swistock saw both the benefits and negative effects of gas- well drilling.

“The economic impact can be tremendous, and the environmental effects can be minimized if we are careful,” he said. “The newer, deeper drilling in the Marcellus shale is different than the gas-well drilling we are accustomed to, and it’s happening very quickly.”

“We need to adapt our regulations and strengthen our regulatory agencies to make sure we are prepared to protect our water resources.”